Visual Sovereignty: Charlotte Richards and Taloi Havini

An essay that I wrote in my second year at Emily Carr, Visual Sovereignty inquires into the power dynamics of photographic representation contextualized by settler-indigenous relations. Looking at the images of Edward S Curtis, Charlotte Richards and Taloi Havini, I explore the double-edged sword of photographic representation: a mechanism of violent oppression on the one hand, and a tool of resistance on the other.

April 2020

The history of Indigenous representation within photography – most notably in portraiture – is one fraught with various subtle complexities surrounding the implications of the subject / photographer relationship. Early missionary photographs, for example, function to reinforce notions of western modernity, while Edward S. Curtis’ widely known portraits of Indigenous communities mystify and stereotype, conjuring notions of authenticity. Anthropological and ethnographic images, on the other hand, in the early twentieth century have been “inextricably connected with policies of assimilation, eugenics and anti-miscegenation, and to the making of racial categories (Smith and Hughes, 2).” Though photography has had largely negative connotations towards Indigenous identity historically, it is a medium that is now necessarily embedded in the very fabric of semiotics and cultural production – a powerful tool, and maybe even a weapon, in the right hands. It is within this context that a mechanism once used to suppress and misrepresent may be reconceptualized and repurposed as a mode of visual sovereignty.

Before continuing, we must first acknowledge that, regardless of who is behind the camera, the very nature of portraiture is inherently staged – ironic, as this is contrary to portraiture’s function to reveal truths. This staged nature is overtly apparent in the work of photographers such as Samuel Fosso, Nikki S. Lee, Cindy Sherman, and many others, but is less visible in the work of photographers that are considered to operate within a purely documentarian context – and perhaps for this reason alone, it is dually important that we recognize what these images attempt to construct. Intentionality and audience become key. Consider Edward S. Curtis’ Oasis in the Badlands, an image that depicts Red Hawk, an Oglala warrior, looking off into the distance while sitting on a horse that is drinking from a small pond in the Badlands of North Dakota. What makes this image problematic is that it functions as the embodiment of the “noble savage” ever present in the collective memory of North America. When we consider that Curtis also set out to photograph what he thought was a dying race, Oasis in the Badlands, and much of his other images then attempt to firmly establish Indigenous cultures – and peoples in the past.

Curtis, Edward. “Oasis in the Badlands”, 1905.

Early landscape photographs in North America certainly helped reinforce this notion – presenting pristine, sprawling spaces that excluded any presence of their original inhabitants. Author T.J Demos, on the subject articulates that “landscape has a long art historical tradition – and the tendency to portray “nature” as a separate realm, defined by the absence of humans and highlighting the beauty of wilderness, has been endlessly repeated. Landscape images tend to support the expansive colonial project, driven by the art market or commercial journalistic imperatives, sometimes unintentionally, by practicing the objectification of the nonhuman into a commodifiable picture that can be possessed within economies of wealth accumulation (Demos, 46).” There is much room for extrapolation on the subject of constructed landscapes (Demos continues to discuss racial and class privileges, and much more), but for the sake of cohesion, I will leave it there. The point is, both portraiture and landscape had an irrefutable part in constructing a very specific set of images with a very specific purpose: to define and display a dying people and the vast North American landscape that would be for the taking once they were gone – framed so as to establish the perspective of the photographers as singularly true.

What is largely missing from these accounts is the voice of the subject – active contribution and agency. Photographs captured by settlers were and continue to be far from innocent – they serve to define what Indigenous people are supposed to look like, how they dress, where they live. These representations have had long lasting repercussions and create a hegemonic backdrop to which Indigenous people today are compared to, as if to say, “the modern Indian is not an authentic Indian.” Which is a preposterous notion, given that these are not images of self-representation – and in fact, there are plenty of examples of Indigenous photographic self-representation historically. They’ve just been excluded from popular memory, which is certainly reflective of their contrasting stances on what Indigeneity actually looks like – they do not correspond with the reality that settler photography attempted to create.

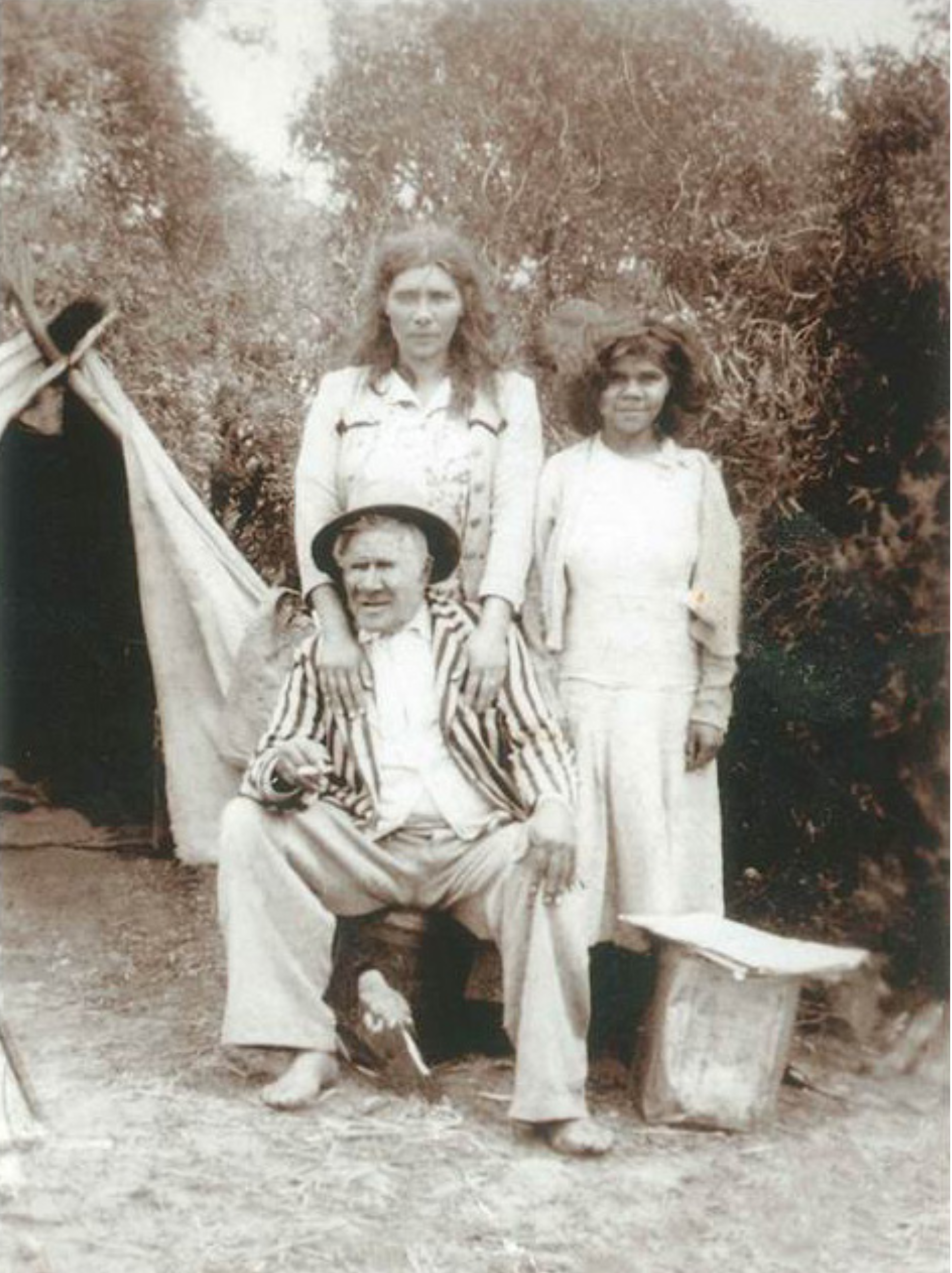

Charlotte Richards, one of the earliest documented Australian Aboriginal women photographers, is an excellent example. Working in the 1940’s through the 1980’s, Richards focused primarily on Ngarrindjeri fringe camp communities on the edges of white settlement. These camps were situated on the outskirts of towns and became critical sites for maintaining connections to the land, oppositional knowledge, and various other pedagogical practices. In one image, Richards depicts her aunt (Isabel Koolmatrie), her sister (Irene Richards), and her grandmother’s brother – Joe Walker Jr. At the bottom centre of the frame is a pet Magpie.Whereas the settler photographs are often dramatized, this image is imbued with warmth and intimacy – the subjects looking directly at the camera as if to reclaim ownership over not only the photographic space but extending beyond. They are not objectified in any way, and as discussed previously, although this is a staged portrait, it is far closer to reality than any settler depiction. The subjects are not presented as part of a dying race, nor are they examples of the success of the colonial project. They in turn represent Indigenous modernity and resilience, the backdrop of the fringe camp serving to instill the prevalence of self-determination.

“Uncle Nulla (Walter) Richards, his daughter Irene Richards (mother of Walter Richards, and Iris, Ruby, Jeffrey and Robert Hunter) and Uncle Poonthie (Joe Walker), One Mite”, c. late 1940s early 1950s

While oral storytelling and passing of knowledge is irrefutably paramount in the continuity of Indigenous cultures, it must be acknowledged that the technical image is now the dominant form of abstracting the world, and therefore the narratives that they create – and the ways in which they can be utilized to articulate the nonphysical – are absolutely and inextricably tied to future Indigenous survivance. Visual illiteracy, especially within this context, is incredibly dangerous for both image makers and the those on the receiving end. In order to repurpose the technical image, we must first come to understand it - we have examined two examples of the implications of technical Imagery thus far, one from a colonial perspective, and one from an Indigenous perspective. Both historical. It’s fair to say that we can conclude that the communication of the intent behind the two contrasting views are fairly straightforward. Contemporary examples, on the other hand, tend to be more complex, as they operate in a much more subtle manner. This is where unpacking and disseminating becomes an essential skill.

The images created surrounding the Standing Rock protests are useful for our thinking here. Much of the curated catalogue of #NoDAPL images are meticulously and intentionally created with direct knowledge of western logic, avoiding any framing that would fall into settler-colonial tropes or archetypes, in turn creating a body of powerful images that work to undo any falsely constructed realities. “There are no vast uninhabited landscapes under dramatic clouds, no warriors on horseback, no nostalgic filters. Instead they emphasize community, land-based activity, creativity, and everyday resistance. They challenge western chronologies by setting together elements of the past and present and by connecting these to a future of struggle and survivance. (Brigido-Corachan, 79).” Though for every image that accomplishes this achievement, there is a poorly thought out counterpart to match – primarily (but not exclusively) captured externally by non-native photographers. Much come from a sincere place but end up contributing to the very tropes that the photographed communities actively attempt to refute. Furthermore, these counterparts focus largely on the materiality of the movement – perhaps in part due to the false preconception that the photograph is an instrument to uniformly inscribe reality – making little or no effort to embody the spiritual or more abstract facets of the interrelationship between people and land. Problematically, it is not always easy for the untrained eye to separate the two forms of representation mentioned here – even more concerning is the fact that much of us may not even recognize the exchange of information taking place and the biases and altercations to our individual and collective memories that form as a result.

Which brings us to the final body of work that I would like to discuss here: Taloi Havini’s Blood Generation, a series of portraits made in collaboration with photographer Stuart Miller (Havini’s cousin) that effortlessly bridge the past and the present to create the pinnacle of photographic sovereignty, while simultaneously breaking down the constructed reality (or realities) that have existed and continue to exist. Some foregrounding: The work centers on Bougainville Island in Papua New Guinea, a region that has seen immense conflict following external interest in mining. In the 60’s, even before Papua New Guinea got its independence in 1975, Australians were already digging and mining in Bougainville. In their explaining to Indigenous land owners what crown law was, they said “anything six feet under the earth? It belongs to us.” After the arrival of the Paguna Copper Mine, civil war broke out in 1988, and the copper mine subsequently closed the following year, but the damage has been long lasting, and threats to reopen have been discussed in recent years. Havini and her family were forced to flee and sought refuge in Australia in 1990, and while she was in high school her father, Moses Havini, attended a lot of protests and activism meetings for the self determination of Bougainville – for an intervention of human rights to come in. For one of his meetings, he went to the Solomon Islands, and came back with a cassette tape labelled “Blood Generation” – a name given to the generation of Bouganvilleans who were born into war. The tape covered what it was like to grow up in conflict behind the blockade and became the main source of inspiration for the photographs discussed here.

We will examine this series in the same framework that I used to introduce Curtis’ images: as constructed reality – to answer the questions of intentionality and intended audience. First to note is that, unlike Richard’s images, Taloi and Stuart’s are not full of warmth, nor are they intimate. Upon first viewing, it may even seem that they are distant, cold, and framing the people photographed in a dramatized and tragic way. This is because contextually, the subject matter is inherently dramatic and not without tragedy, but rather than focusing solely on this negative history, the artists use it to point towards something else: the Bouganvillean youth are not depicted as being part of, as one Australian patrol officer put it “a ruined people” – merely an unfortunate byproduct of western progress – but rather are incredibly strong and profoundly determined. The intention of the work, Havini notes in an interview with QAGOMA (the Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art), is to “create a new language around the history of photography on indigenous peoples – which has been a predominantly negative one.” The audience is not solely colonizers, nor solely Bouganvilleans, but invites both. Additionally, the images are not tethered to the materiality of Bougainville (through the physicality of the mining is certainly a large part) – but reach beyond, most visibly in relation to water – perhaps more reflective of Standing Rock’s “water is life” phrase than much of the images that emerged from the movement.

Havini, Taloi. “Lillian, Daantania South Nasioi Region.”

“People are going to know who they are.” The sentiment, articulated by Havini, seems to me representative of the core of the portraiture of marginalized peoples and communities. Even though we can obviously never truly know a person through an image, a well-crafted (a well-constructed) image can certainly produce an illusion of intimate knowing. An excellent image can facilitate understanding, purely through visual information. Nonetheless, it is still a kind of illusion – akin to a translation of being – a slight of hand that is truthful at times, and dishonest and misleading at others – a paradoxical device that can call upon the nonphysical through the purely physical – a mode that is at once as much about what is seen than what is not. The duplicities carry on, but the most important take away is this: the photographic space is contested, and will continue to be contested. Accessing one end (truthful representation) does not restrict entry from the other (dishonest and misleading representation). This goes for both the photographer and the interpreter. The technical image will play a critical role in Indigenous continuity as a mode of visual sovereignty, but it will also continue to operate within its well-worn status as a suppressor and a conduit of misrepresentation – most likely in an increasingly subtle manner. What is critical now is that we pay very close attention to what images appear where, in what context, and with what intent – and which images are excluded – photography after all, is a language. Removing or adding even a single word or arranging a sentence in a certain way can have grave implications.

Works Referenced

Works Cited

Flaherty, Robert J. “Nanook of the North.” (dvd) Criterion Collection, x.1998. ISBN 1559408690. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=shib&fb=cat04308a&AN=ECUAD.101103411&site=eds-live.

Grimshaw, Anna. “Who Has the Last Laugh? Nanook of the North and Some New Thoughts in an Old Classic.” Visual Anthropology, 27, 2014, p. 421-435.

King, Thomas. “The Inconvenient Indian.” Anchor Canada, 2012.

Lydon, Jane. “The Flash of Recognition Photography and the Emergence of Indigenous Rights.” Australian Historical Studies, 44, 2013, p. 294-295.

Nanabush, Wanda. “Notions of Land.” Aperture Magazine, Vol. 234, 2019, p. 73-77.

Prado, Emily. “Sovereignty Through Photography”. Bitch Publications, Issue 63, 2014, p. 7.

Thomas, Kylie. “Decolonisation is now: photography and student-social movements in South Africa.” Visual Studies, Vol. 33, 2018, p. 98-110.

Waldroup, Heather. “Indigenous Modernities: Missionary Photography and Photographic Gaps in Nauru.” The Journal of Pacific History, Vol 52, 2017, p. 459-481.

Brigido-Corachan, Anna M. “Material Nature, Visual Sovereignty, and Water Rights: Unpacking the Standing Rock Movement.” Studies in the Literary Imagination 50.1, Georgia State University, 2017, p. 69-90.

Demos, T.J. “Art in the Anthropocene.” Aperture Magazine, Vol. 234, 2019, p. 45-51.

Flusser, Vilem. “Into the Universe of Technical Images.” Electronic Mediations, Vol. 32, University of Minnesota Press, 2011, p. 3-60.

Hughes, Karen and Smith, Cholena. “Un-filtering the settler colonial archive: Indigenous community-based photographers in Australia and the United States – Ngarrindjeri and Shinnecock perspectives.” Aboriginal Studies Press, 2018, p. 2-18.

McDougall, Ruth. “Taloi Havini: Reclaiming Space and History.” Ocula Magazine, 2020. https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/taloi-havini/